Review by Hannah Star Rogers

If I could write this to you on crescent wings folded into doilies from another time I would, but it would not be slick with the eels of modernity. If I could tell you that a word you already know well is about to change, it would not reflect the mirror of traditions in the poetry of surprise. If I could write this to you with a grammar that gave you new meanings I would, but it would be less complex than the beautiful (and for once we can all really mean that together), eclectic poems Elizabeth Metzger has wrapped into four sections and delivered to us like an otherworldly picnic.

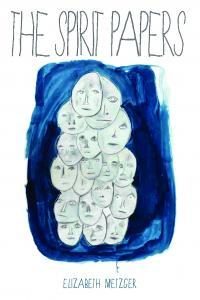

It’s difficult not to tell you what an ethereal and fleshy book this is because reading a master work always makes us want to speak in the voice of the poet now residing in our heads. The Spirit Papers (2017) was published through the University of Massachusetts Press in celebration of Metzger having received the Juniper Prize for Poetry. It’s hard not to think of another Amherst poet faced with Metzger’s title and the press imprint, and with lines like these from ‘Tinsel Demon’, our association is born out:

Before I had to live in an enormous body in a miniscule world.

I took my round existence with no ledges to perch on.

Metzger is the poetry editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal, and it shows in her references and in her flowing concision that leaves nothing unwanted to the imagination. Metzger’s title poem introduces the range of her vocabulary (which will contain dinosaurs, platelet-colored water, and thunders gathering under skirts) without giving away the many things we are going to learn about the contemporary enchantress and her beloveds who inhabit The Spirit Papers:

You dream of me writing

Your name on paper

Adding in pencil live.

You dream a lit match.

The Spirit Papers is remarkably cohesive for a first book, and references itself without tangling with the plague that blackens so many first book writers: the need to display the journey or at least some sense of ‘growth’ in order to construct a narrative that readers will recognise. However well meaning, this often makes the moves predictable, but predictability is something Metzger only serves us when it allows her poems to comfort the reader with a refrain. Poem after poem with titles like ‘Expecting A Death,’ ‘Pre-Elegy,’ ‘Not Spring,’ and perhaps best of this type ‘The Elephant in Your Room’, promise us ground we have covered before, but adhere to the rules of the unexpected, and reveal that sorrow always finds us in strange places: ‘Your first bone’ rediscovered in a hotel shower with its ‘soft deformed ambitions’ that make the point ask ‘how much you discovered/ by loving, and how much you lied.’

Being known before anything is said is decidedly not the work of this text. At the same time that we are coping with so much intricacy in so many approachable lines, we are also dealing with the looming fact the poet is working through: the death of Max Ritvo. His life and friendship are celebrated in the book in ways those who knew Ritvo will immediately appreciate, but which also go to the still point of loss every person who has been lucky enough to find a soul twin experiences in being separated.

Being known before anything is said is decidedly not the work of this text. At the same time that we are coping with so much intricacy in so many approachable lines, we are also dealing with the looming fact the poet is working through: the death of Max Ritvo. His life and friendship are celebrated in the book in ways those who knew Ritvo will immediately appreciate, but which also go to the still point of loss every person who has been lucky enough to find a soul twin experiences in being separated.

We can’t really read Metzger’s book in completion without Max Ritvo’s Four Reincarnations (Milkweed, 2016), and she doesn’t ask us to. Instead, she dedicates the book to both Ritvo and her partner, and then invites us to indulge a too-brief period when two very active poets had something important to discover with each other. Each poet gives us parenting poems. Metzger’s complex relationship with the possibility of bringing another life (which we simultaneously read as another poem) into the world in poems like ‘The Maternal Instinct’ and ‘Via Negativa’ echo Ritvo’s interest in the potentialities of offspring and even his extensions of parentage in poems about medical treatments such as ‘Poem to my Litter.’ The winding interest in what children mean before we have them lets readers consider what promises are and what future expectations we all have, and in the context of Ritvo’s illness and the prospect Metzger faces in losing an artist-confidant of poetic proportions, these exercises of possibility take on new meanings.

There is a science to the magic of the philosophy of Metzger’s poems. Her Romantic tuning pulls the meanings she reflects into the world back at her with such flashes of insight that readers sense that they are not the only ones astonished by what her word turns can do. Deeply held or known phenomena of the body and mind often get their evidence from the natural world, as in these lines from ‘Cargo’:

The sky has the salt impediments

Of thought. It wants to know

Just what exactly it thinks,

But we know the sky is a fact,

just gas and distance, an observation…

The poem finishes with lines true to the nature of poetic love and the very real love in Metzger’s work:

We think of what we once were,

a bypassed island

we carried into our guilt.

Once I loved you simply because

it made me feel truthful, like a ship.

Now I love without integrity.

There is no depth but there is

because the ship is going into it.

Hannah Star Rogers’ poems and reviews have appeared in The Kenyon Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Tupelo Quarterly, The Carolina Quarterly, and The Brazenhead Review. Her flash fiction has been honored by Nat. Brut and Glimmer Train. She received her MFA at Columbia University, her PhD at Cornell University, and is currently a visiting scholar at the University of Edinburgh. She has received the Akademie Schloss Solitude Fellowship in Stuttgart, Germany, Djerassi Artist Residency in Woodside, CA, the international artist residencies at ArtHub in Kingman, AZ, the Arctic Circle in Finland, and with National Park Service in Acadia, Maine and the Everglades, FL.