the skin of my teeth

For a couple of weeks in October, I mainly trudge back and forth from the dentist. I’m unemployed and about to leave Edinburgh – the city I have lived in for six years, or all of my adult life. Some of the days are unseasonably warm, but often I leave my flat in sandals and rolled-up jeans and watch as my toes turn purple after dusk, somehow surprised at the summer ending, and at my inability to manage the external world’s effects on my body.

It feels appropriate to be suspended in a kind of limbo between jobs and cities as the nights slowly close in, as the temperature drops. I move from room to room in my high-ceilinged flat. I clean the kitchen, discard things. I measure out my days in job applications, packed suitcases, and dental appointments.

When I was eighteen, I fell on my face. I had been drinking with my boyfriend at the time, trying to impress him by watching football after work and keeping pace with his friends’ pint rounds. He was a few years older than me, and managed the restaurant where I worked as a waitress. It hadn’t been long since we started sleeping together and I still didn’t believe that it might continue.

That evening we go back to his house, where I would sit on the kitchen countertops, in the corner, while he washed his housemates’ dishes. The house was sparse and functional in the way most living spaces shared by men in their early twenties are. The tables and chests of drawers were always scattered with tobacco, receipts and loose change. Later that year, I would help him take his bed frame apart, carrying the pieces downstairs and through the overgrown garden to the shed, leaving his double mattress on the floor. At the time, the freedom he had to do this thrilled me. In his presence, I often imagined myself older, and somehow unshackled. Yet, I already adored him, and this conversely only made me feel young, anxious, and small.

That evening, sliding off his countertop, I step across the black slate tiles, moving to the faux leather sofa at the other side of the room. He pours me a glass of wine. I do not feel drunk, but I must be. Six months after being discharged for eating disorder treatment, I am still thin, and we have been drinking for hours. He sits next to me on the sofa. I am aware of the heat in my cheeks, the pitch at which I’m laughing. He stands up, holds out his arm, takes my hand. He pulls me up from the sofa, and my socks slip on the slate. I can’t get my hands out in front of my face fast enough.

When I stand, he looks shocked and scared. I laugh, I try to reassure him. But my mouth doesn’t feel right – I can taste metal and my lips feel sharp. My front tooth is broken in half, my lips cut and bleeding. It wasn’t your fault. The room feels colder than before, and suddenly dark. It wasn’t your fault.

He crouches down on the ground, searching for shards of enamel under the side table, the fridge. I am thankful for the alcohol I’ve drunk, because my mouth doesn’t hurt as much as I’d expect it to, aside from a persistent stinging in my lips. I wish he would stand up and laugh the whole thing off, or forget it happened completely, like I am still trying to. I’m fine, really.

I take two paracetamols and we go upstairs to bed, the piece of tooth he found pressed in my palm. All I feel is a high-pitched desperation that this incident won’t repulse him. We put on an episode of something, and I press my back against his body, my damaged face turned away from him. I run my tongue over the jagged edges of my front teeth. We have sex. My lips throb and I don’t fall asleep for a long time.

Dreams about teeth are very common. Specifically, teeth falling out. It is generally accepted that dreams of this kind are symptoms of stress, but the exact contours of this stress are unsettled. A fear of saying the wrong thing, of spitting out embarrassing words. Embarrassment itself, or a significant sense of inferiority. A fear of rejection. Insecurity over appearance, a feeling of ugliness. A fear of aging, of losing sexual power, of losing femininity. Troubled communication.

I regularly have dental dreams. In some, they all fall out into my hands as I try to catch them. In some, a single tooth wobbles – so convincingly sometimes that I have woken up and pushed my incisors to check I was asleep. Or they crumble to dust. In one memorable dream, I was being driven very fast down a motorway as one by one my teeth dropped out of my mouth and rushed past me like rain.

Are my recurring teeth dreams just how stress manifests after dark? Or are they particularly symbolic to my unconscious? If none of my teeth had ever broken, would I be so hyper-aware of their vulnerability? Do people who have broken their noses, or their arms, dream of these body parts scattering freeways?

The artist Carol Rama specialises in bodies. Her paintings are both erotic and disturbing. Body parts hang in space, disconnected. Tongues, breasts and penises protrude. Clinical beds and wheelchairs populate softly washed out canvases, and limbs distend or disappear. I paint to heal myself, Rama said.

In 1933, when Rama was fifteen, her mother was admitted to a psychiatric clinic. Rama said she was fascinated by the female patients who wandered the halls, often undressed. Their flesh was uninhibited, even if their bodies were institutionalised and their mental states under surveillance. Rama began her drawings then.

In 1933, when Rama was fifteen, her mother was admitted to a psychiatric clinic. Rama said she was fascinated by the female patients who wandered the halls, often undressed. Their flesh was uninhibited, even if their bodies were institutionalised and their mental states under surveillance. Rama began her drawings then.

In one, a womanish body crouches, tongue out, defecating copiously. In another, two decapitated bodies seem to jerk off towards each other. But, of course, the ones that draw me most are full of teeth. In Opera no.18 nine upper jaws hang, each differently distorted. The teeth are crooked, but glaringly white against the yellowed background. They are outlined in red, like they have all been brushed too hard. Five of the gums are thin and curled into twisted grins. I paint to heal myself, Rama said.

In Edinburgh, I leave the dentist’s office with a black pencil case full of syringes. After a week of lisping and snagging my tongue, the tooth that broke in half was fixed with composite, but over the following years it has steadily grown darker. When I saw photos of myself with a fraction of grey peeking through my lips my stomach would drop. I would zoom in on others’ teeth, fixate on celebrity dental work, Google search ‘the perfect smile’. I felt vain. I smiled with my mouth shut.

I had been told that the only way to fix the tooth was with veneers. A solution that, on a student’s budget, was no solution at all. But then a new dentist with kind eyes drilled a hole into the back of my broken tooth, pressed putty against my gums, and handed me whitening gel and perfect plastic replicas of my jaw. I am to squeeze gel inside my darkened tooth with a syringe and seal it in with a gum guard. I am to do this for two hours, every other two hours, for four days, before beginning to whiten the rest of my teeth. The dentist with kind eyes, who asks me about my job applications and shakes my hand every time I leave his office, hopes that this will lighten the tooth enough to not need veneers. He hopes that in just a month I will be able to smile without twinges of shame.

Before I leave, the dentist’s assistant gives me two curved plastic implements. I put them in my mouth and pull on the handles, stretching my lips away from my teeth. Like a dog growling. The dentist holds a large camera close to my face and takes some photos. I am aware of my lipstick, now coating the hard, blue plastic of the implements. I am aware of saliva pooling in the hollows at the sides of my mouth. The dentist with kind eyes loads the photos on his computer screen and turns it towards me. The photos fill the screen; my lipstick is just visible in the corners. My gums are pale, in places pulled tight almost to whiteness. The dentist looks at me, seeking approval for his high-resolution pictures. In the centre of the screen my grey tooth glares at me. The line dividing real enamel from fake is clear, diagonally bisecting the tooth. I return the dentist’s smile, mouth closed. I put the syringes in my bag and walk back to my emptying flat.

As a child, Rama visited an aunt who took her teeth out at night. Her grandmother had false eyes; her uncle sold orthopaedic goods and gave her false limbs as toys. She was surrounded by lost body parts, lost persons, and by false, excessive limbs. Are the teeth in Opera no.18 meant to be fakes? Where are the lower jaws?

Until the mid-nineteenth century, most false teeth were made from ivory, or from human teeth. Real teeth were extracted from soldiers’ corpses or executed criminals, or sold by the dreadfully poor. After the Battle of Waterloo, “Waterloo teeth” were in particularly high demand. Often these would be riveted into a base of animal ivory, or mixed with parts of horse and donkey teeth. The first porcelain teeth were judged too white to be convincing.

When I was twelve, my orthodontist discovered that two of my deciduous teeth had never been shed. In the corners of my lower jaw, the penultimate teeth are small – half the size of those next to them. Apparently this is rare, but not quite as rare as most people think. My mum has one; I have two. Perhaps my child will have more, or perhaps the dental quirk will end with me. My orthodontist wanted to cut open my jaw and put a metal plate inside, to stop the milk teeth sinking into my gums like rocks in quicksand. My orthodontist looked like Christopher Lee and did not put his fingers in my mouth gently. I said I didn’t want a metal plate in my jaw. He said it would be more expensive when I was older, and I should hope to marry rich.

I tried to say that women could make money too these days, but his thumb was on my tongue.

When teeth were still ruled over by barbershop surgeries, barbers would file down the teeth and apply acids to whiten them. The acid would coat the enamel, and sink into the root. This made the teeth lighter, but also eroded them over time, leading to more decay.

After filling my tooth cavity with whitening gel for three days, I begin to see the enamel lightening. At least, I think I do. I stand in front of the mirror in my bathroom, pull back my lips. I stare at the tooth, trying to remember its original shade. The bottom half of the tooth – the half made of composite – remains grey. I take photos of my teeth, zoom in on the fault line.

The syringes of gel come with a booklet of warnings. It says to wash off the gel after ninety minutes, and not to exceed this time. The dentist with kind eyes told me to ignore this advice. The booklet also says that the gel can cause irritation to the gums, that it should not be swallowed. It usually takes me a couple of attempts to inject the gel into the back of my tooth, and, each time, some gets on my tongue and the roof of my mouth. It tastes sweetly bland, but makes my tongue tingle slightly.

After four days of focusing on my broken front tooth, I begin squeezing small drops of the gel into my plastic replica jaws. At first, I do as the booklet says and apply one drop to each corresponding tooth, before clicking the retainers into place. Soon though I get impatient, and begin squeezing in as much gel as the gums will allow.

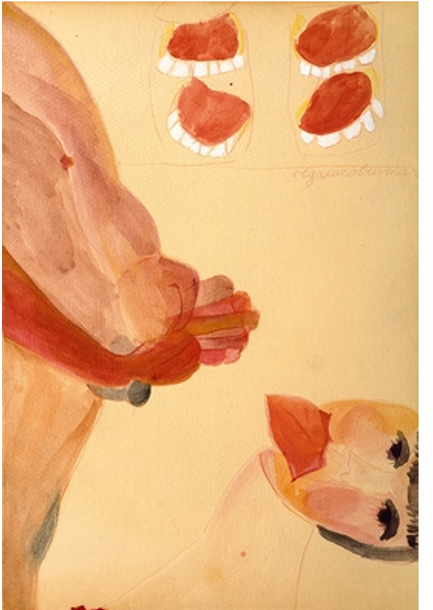

Rama’s disembodied upper jaws populate another work of hers. In Opera no.9, four jaws (or is it two sets?), hang in the upper right corner. Faint lines circle the jaws into pairs (two sets?), and one underlines them. The teeth are lined off from each other, and from the rest of the painting. They are separate, but involved.

Rama’s disembodied upper jaws populate another work of hers. In Opera no.9, four jaws (or is it two sets?), hang in the upper right corner. Faint lines circle the jaws into pairs (two sets?), and one underlines them. The teeth are lined off from each other, and from the rest of the painting. They are separate, but involved.

Directly below the teeth, in the bottom right corner, a face is turned sideways. The neck is tilted up, the black eyes in line with the edge of the paper. The mouth gapes, and a thick red tongue protrudes, reaching up in the direction of the floating teeth.

On the left side, a headless figure. Two arms – the closer one a deep, bloody red – extend from a hidden point; a single rosy nipple seems to peek out from a chest. The hands hold out multiple penises like a bouquet, over the lower figure’s red tongue. The red of the tongue, the arm, the gums, and two of the penises match. Rama said the colour red reminded her of her desire to be a bullfighter. The red is provocative, courting violence.The white grins in the top right jump out, like bulbs lighting the scene.

Violence, voyeurism and eroticism all compete, merge and are made strange in Rama’s painting. A headless figure looming over a bodiless head – is this one person, torn apart? The teeth seem to emerge unbidden, like repressed matter surfacing in a dream.

In the week after my tooth first broke, one of the staff at the restaurant where my boyfriend and I worked made jokes about the accident. He would joke that my boyfriend must have pushed me down the stairs, or hit me in the face with something heavy.

He laughed a lot each time he said something like this, and we would laugh too. I assumed he found it funny because he thought it was unimaginable.

I wondered, if this had been what happened, if I would have said anything.

I sit alone in my stripped out flat with gel on my teeth, listening to true crime podcasts. My flatmates moved out a week or two ago, so I can walk around undressed or unwashed, teeth sheathed in plastic, all day and with impunity. I have no schedule or commitments, aside from rinsing off the gel and brushing my teeth every two hours, before refilling the retainers two hours later. I listen to stories of women being murdered – by their husbands, their boyfriends, colleagues, friends and strangers. Sometimes they can only be identified by their teeth.

At my first appointment with the kind-eyed dentist, he peered into my mouth and told me I had a lot going on in there. I felt a need to explain, or to apologise. I have always been aware of my mouth as a problem. A mix of stubborn deciduous molars, broken front teeth, and plastic caps gave me a dental identity of too much.

The etymological root of dental is dens, the Latin for tooth. Identity comes from identitas, and, earlier, idem, Latin for the same. But don’t they sound the same.

Palm reading is more popular, but the shape of the teeth can also be read to determine personality. In morphopsychology, there are four essential teeth shapes, each with corresponding traits, strengths and weaknesses. Square teeth for people who like order – who are level-headed, diplomatic and calm, but with an entrepreneurial spirit. Triangular for the carefree, impulsive, free spirited extroverts; oval for the reserved, perfectionist, artistic introverts. Rectangular for the determined, the intensely passionate – for people with explosive tempers and imaginations.

Milk teeth are thought to be the harbingers of a child’s destiny, specifically the problems they will face as an adult. If milk teeth do not drop out for a long time it indicates future infantilism.

There are identity traits attached to smiles too. Gapped for lust and sense of humour. Bucked for timidity. Large front teeth for rigidness, and small for kindness. I zoom in on the photos of my teeth, flipping between before and after the whitening process began. I cannot tell if my teeth are small; I do not know if I am kind.

A few more days into the process, and I wake up with my teeth stinging. The booklet I have been ignoring warns about tooth sensitivity, but I was not prepared for the sharpness of it, or for the throbbing in my lower jaw. The tips of my bottom teeth feel, somehow, raw. I had been expecting a sensitivity similar to biting into ice, but this is more a shrill ache. It distracts me from my thoughts. It persists throughout the day.

My upper teeth seem unaffected, until I push the plastic retainer filled with gel into my gums. My eyes immediately fill with tears. Where my teeth meet my gums, it feels like burning. I think of Rama’s red-lined teeth. I think of the barbers pouring acid onto filed enamel. At that moment, it feels like not much has really changed.

I try to escape the pain in my jaw by walking the streets. I take my crime podcasts with me, plugging them in at the highest volume to drown out the sound of cars, the sensation of my teeth. I press my tongue down hard on my bottom teeth, as if trying to push them back into my skull. This is the only thing that slightly dulls the stinging. I’m fine, really.

Rama said that she sought to improve the body, and give joy and meaning also to those that are deformed. In debased, diseased bodies I was looking for a spark, a flash of vitality, a desire, even obscene, to exist.

She said she was happy and secure until she turned eight. Then she became a kid scared of existence.

She also said, you can live without fear only up to the age of twenty.

Trying to distract myself from the pain in my gums, I find myself in a bookshop, wandering through the art section. A set of shelves holds a set of vividly coloured titles, obviously an official collection of some kind. I study the books, tracking them from crimson to aquamarine. I find all the usual suspects: Picasso, Matisse, Monet, etc. Three of the covers have paintings of nude women in the centre. Not a single one seems to be a study of a female artist. I walk away from the shelves.

The stinging in my teeth makes it hard to focus on things properly. I don’t have the mental energy to look at titles in a considered way; making decisions seems like too much effort. I pull a book from a shelf at random, open it at random. Carol Rama stares back at me. I turn the page. Her disembodied, floating teeth hang there. The gums seem even more lurid against the paper’s white gloss.

Rama explained her interest in teeth, saying, at home we had an aunt who had had all her teeth pulled out by the vet when she was a girl. She always wore a set of false teeth, even as a kid. Since there were all these false teeth lying around, I was always drawing them.

Rama said she preferred my aunt’s false teeth to any flower: I hate flowers, really hate them, perhaps because they are more beautiful than my paintings, than me.

She said, it’s mainly anger inside me.

She also said, Are you living in hell? Well, try to make the most of it, even there.

I close the book. I walk away from the shelves.

Eloise Hendy is a writer and poet living in London.She is currently working on a PhD on autotheory, creative labour and the contemporary at the University of Sussex. Her writing has appeared in Frieze, Ambit, PAIN, The Tangerine, and The Stinging Fly, among others, and she was shortlisted for The White Review’s ‘Poet’s Prize 2018’. Her debut pamphlet, the blue room, is available from Makina Books.

Continue to Iain Britton’s ‘existence of a passion flower’ & ‘toffee apple’ >>