Review by Lewis Wood

‘Creature, what is it that you want?’, Grandpa Fred asks. ‘Civilization,’ the Gremlin responds, ‘the Geneva Convention, chamber music, Susan Sontag; everything your society has worked so hard to accomplish.’ This scene in Gremlins 2 speaks to the central position Susan Sontag held within the American public imagination during her lifetime; she epitomised intellectual achievement in the contemporary west and her surname possessed the instant recognisability that accompanies fame of the highest order (alongside Christ, Michelangelo, and Madonna). But so, too, does this scene prognosticate the difficulties which generations of readers have since faced in reckoning with a writer whose place in the zeitgeist vastly outshone the attention paid to her work.

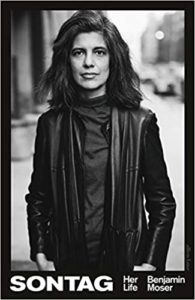

Benjamin Moser acknowledges the challenges of dealing with ‘America’s last great literary star.’ There is Sontag the symbol – or in Moser’s parlance, the ‘metaphor’ – and Sontag the person, the writer around whom the reputation has accumulated. Moser defines the symbol in his introduction: Sontag was the first woman to combine ‘the mind of a European philosopher and the looks of a musketeer,’ supplying a model of female modernity and authorship ‘for generations of artistic and intellectual women […] more potent than any they knew’; she was super-human, ‘Athena, not Aphrodite: a warrior, a “dark prince”’; she ‘became famous as a one-woman dam, standing fast against relentless tides of aesthetic and moral pollution.’ Once the symbol has been described, it can be dismantled; throughout Sontag, Moser charts Sontag’s personal and intellectual development whilst remaining ever conscious of what she came to represent and investigating how such an image was constructed.

There is no sparsity of literature about Sontag. Amusing anecdotes of her infamously errant behaviour during her time as Manhattan’s ultimate socialite appear in countless memoirs which accumulate to present Sontag as the intelligentsia’s answer to Princess Margaret; the result diminishes our understanding of her personhood and distracts from her writing. Biographies produced by those close to Sontag are equally unhelpful. Sigrid Nunez, the former partner of Sontag’s son, David Rieff, attempts reification in Sempre Susan: A Memoir of Susan Sontag, but the book is rife with pernicious accounts of melodrama. Rieff follows suit with Swimming in a Sea of Death: A Son’s Memoir, which focuses upon Sontag’s death in 2004, but the pitiful image he presents of Sontag at the end of her life bears little relation to the way she lived it. Both accounts represent the corpus by which the Sontag symbol is sustained.

Others have fared better, including Nancy Kate with her documentary film, Regarding Susan Sontag, and Daniel Schreiber in Susan Sontag: A Biography. Kate interviews Sontag’s family and friends to great effect but is confined by the time limits of the film medium, resulting in a paucity of detail. Schreiber’s biography is the first substantial attempt to demarcate the Sontag symbol, but it suffers from a lack of access to Sontag’s archival writings; Rieff published the first of three volumes of Sontag’s journals and notebooks, Reborn, in 2008, the year after Schreiber’s biography was released.

Moser was a logical choice to navigate the complexities of Sontag’s image in this authorized biography: his debut, Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, distinguished him as a writer with the capacity to disaggregate the complex interfaces between a writer’s life, oeuvre, and reputation. But there can be no doubt that whilst Sontag benefits from Moser’s skill, it also derives authority from his unique access to archival writings upon which many of its conclusions or revelations are predicated.

Sontag, Moser writes, ‘rejected her past’ and had an ‘inability to perceive the difference between fantasy and reality,’ as a result of which details of her early years have evaded biographers – until now. Moser enriches his text with descriptions of the books Sontag consumed in her childhood, satiating both casual readers looking to follow in her footsteps and academics charting the development of her style. There are surprising early influences: as a child, Sontag ‘loved the sexy swashbuckler Richard Halliburton’ and idolised Jack London. The Europeans followed, and Moser describes Sontag stealing Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus from a local bookshop, and holding forth on Kant, Nietzsche, and Freud whilst still in school.

Moser also pays close attention to the development of Sontag’s bisexuality, and one of the major triumphs of Sontag is the convincing reclamation of Sontag as a queer icon. Sontag critics have maligned the hypocrisy of a writer who refused publicly to acknowledge her queerness whilst insisting that ‘radicalism meant possibilities for personal freedom and self-creation.’ Moser reminds cynics that such acknowledgement would have resulted in harassment and, potentially, the loss of child custody. It would irreparably have damaged her career, too:

Susan’s growing cultural power, the power of her admiration, depended on being unquestionably established as a universal arbiter. To be known as a feminist, much less as a lesbian, would have pushed her to the margins.

Moser rescues Sontag from disdain, but not from pity. At the age of sixteen, Sontag enrolled at UC Berkeley; there, she read Djuna Barnes’ Nightwood, initiating her entrance into California’s queer subculture, and, in turn, leading to some of her most joyous diary entries: ‘I know how good and right it is to love.’ This is moving to read when contextualised by the repression Sontag was later compelled to exercise, resulting in a life marred by ‘low self-esteem and depression.’

Moser further bolsters Sontag’s liberal credentials by claiming that she nonetheless popularised an inherently queer literary style. Sontag’s journals detailed Polari words and phrases snatched from the queer vernacular; these lists, Moser writes, demonstrate Sontag’s ‘nearly anthropological’ recording of ‘a mode of homosexual sensibility that Susan […] more than any other writer, first brought to the awareness of a heterosexual public,’ particularly via her landmark essay, ‘Notes on Camp’, and its aphoristic style which was modelled upon the pithiness of queer discourse and which she employed throughout her career. Sontag would engage with queer issues throughout her life, Moser reminds us, notably via AIDS and Its Metaphors – ‘the closest [thing] to a gay rights book Sontag would produce’ – and thus Sontag emerges as a person reconciled to her sexuality and committed to advancing queer causes via any safe means.

Discussion of Sontag’s sexuality foregrounds Moser’s greatest conjecture. In 1951, Sontag transferred from Berkeley to the University of Chicago where she met Philip Rieff, a sociologist and faculty member. Sontag agreed to marry Philip Rieff ‘slightly more than a week’ after they met: Sontag aged seventeen, Rieff twenty-eight. Rieff is depicted as controlling and solipsistic. Sontag underwent a back-alley abortion which is described in harrowing terms and, soon becoming pregnant again, Sontag ‘wanted to go back to the abortionist,’ but Philip ‘refused.’ Thus, David Rieff was born in 1952, an event which ‘institutionalise[d]’ Sontag’s submission ‘to the heterosexuality to which she had been such an ambivalent convert.’ It is amidst many such antagonistic characterisations of Rieff that Moser stakes his most significant claim: that Sontag was the true author of Rieff’s magnum opus, Freud: The Mind of the Moralist.

Notably missing from Moser’s argument is the voice of Sontag who never publicly claimed credit, and the testimonies he presents are unconvincing. ‘Susan always regretted signing [the book] over to him,’ Moser writes without a source. ‘Susan claimed she wrote “every single word”’ Moser writes, citing an ‘interview with Sigrid Nunez’ – but Nunez’s first-hand account is less convincing:

She was a full coauthor, she always said […] She sometimes went further, claiming to have written the entire book herself, “every word of it.” I took this to be another of her exaggerations.

Suspicion of this claim being an exaggeration is encouraged by depictions of Sontag as someone who regularly ‘lashed out’ and ‘wanted to hurt someone’ when feeling aggrieved.

Other critics take similar issue with Moser’s treatment of Rieff. Janet Malcolm writes that Moser ‘in no way substantiates his claim’ which is fuelled by ‘utter contempt.’ Len Gutkin is more sympathetic, ceding that ‘most critics seemed to accept Moser’s charges’ and that his evidence is ‘compelling’. Gutkin, however, introduces additional questions of authorship, demonstrating that sections of The Mind of the Moralist were taken without attribution from M H Abrams’s book, The Mirror and the Lamp. This complication does not elucidate its author: Rieff ‘the scam artist,’ or Sontag who, when confronted with allegations of plagiarism later in her career, delivered the unconvincing riposte that ‘all of literature is a series of references and allusions.’ Ongoing uncertainty does not deter Moser, who quotes from The Mind of the Moralist as if it were Sontag’s work, although his attempt to recast this work as part of Sontag’s oeuvre is unsuccessful. Sontag’s ‘habit of exaggeration seemed to infect those who wrote about her,’ Nunez cautions.

Sontag’s writing is addressed with greater tact throughout the rest of the biography. As Moser progresses, he chronologically situates Sontag’s key essays, novels, and short stories within contemporary personal and political events, reflecting upon what their contents reveal about Sontag’s developing style and interests. Sontag was a prolific writer and Moser cannot be comprehensive in his survey, but the texts upon which he expounds are well-selected. An interplay between the UK and US editions of Sontag becomes relevant: Sontag is subtitled, Her Life and Work, in the US, and Her Life in the UK. The UK title is more appropriate, for Sontag’s works are invoked for the revelations they make about their author, not their literary merits. Nevertheless, Moser’s treatment of Sontag’s writing life has scholastic value: there is an insightful commentary on Sontag’s earlier novels, near-universally condemned as failures and thus much neglected; Moser elucidates Sontag’s relationship to the industry and economy of publishing; and he often positions Sontag’s publications within contemporary cultural movements – exploring, in particular, her relation to poststructuralist theories which were en vogue in American academe.

Casual readers, be not afraid; Sontag also includes delicious gossip: ‘Susan’s drug dealers included W H Auden’; she neglected either to wash or brush her teeth; and Jacqueline Kennedy used to invite Sontag over to smoke, but would invariably ‘weep over her lost husband.’ Moser does not hesitate to depict Sontag’s flaws, either: he connects her long-term parental neglect and ‘rages’ to her son’s adult cocaine addiction and psychiatric issues and argues that she horrendously bullied – perhaps extorted – her long-term partner, Annie Leibovitz. Are these displays of inhumanity surprising to anyone familiar with the Sontag symbol? Not at all. But Moser succeeds where his predecessors did not by contextualising Sontag’s tyranny with her capacity for innocence and tenderness: the child who ‘hugged the first saguaro she saw’ when she first arrived in Tucson; the best-friend who read Rilke’s Duino Elegies to Paul Thek as he died of AIDS-related illness.

Such dichotomies are never satisfyingly resolved by Moser, nor should they be. ‘Miss Librarian’ was Sontag’s name for her ‘private self,’ but her interior life cannot be so easily circumscribed and Moser presents a complex psychological profile:

There was the private self: the self when nobody else was around. There was the sexual self. There was the social self: self as representation, metaphor, mask. And there was yet another self: an alter ego who had haunted her all her life, the person she thought she ought to be.

Moser’s refusal ever to provide a definitive answer to the ‘Who was Susan Sontag?’ question is the most superb feature of this book; instead, this biography enables the casual reader to form their answer and provides the scholar with details they need to further their studies. In so doing, Moser cedes that whilst the person was far more complex than the symbol, the symbol will be her lasting legacy: ‘It rose far above her individual life, and outlived her.’

Lewis Wood is in his final year reading part-time for a Master of Letters in Modern and Contemporary Literature and Culture at the University of St Andrews, where he also earned his Master of Arts in English with first-class honours. Since graduating in 2019, Lewis has served as the Executive Officer to the University’s Principal and Vice-Chancellor, and he has worked previously as President of the University of St Andrews Students’ Association.

Continue to a poem by Maxine Rose Munro >>