Review by Jenna Rogers

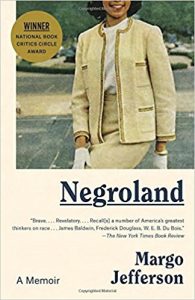

In Margo Jefferson’s memoir Negroland (Pantheon Books, 2015) the author begs for no sympathy as she reflects upon the ways in which her identity has been shaped by the conflicting layers of African American culture of the fifties and sixties. Readers should prepare themselves to be enlightened and provoked by this text.

In dissecting the nuances of her own history–as well as the complex resonances of the word ‘Negro’– Jefferson leaves no stone unturned, beginning the memoir with a detailed lesson in black American history. She reminds us of those who advocated for gender and human rights before their white counterparts began their own activism: James Forten, abolitionist and entrepreneur; Anna Julia Cooper, daughter of slaves and women’s right leader; and W. E. B. Du Bois, writer and intellectual, to name a few. In the memoir’s opening pages, Jefferson’s predominant tone is one of anger, and as she speaks of Ida B. Wells, educator and journalist, Jefferson rages against the fact that black Americans must ask to be respected as humans and fellow citizens:

Proud of their education and cultivation, they are angered and ashamed to be classed with “the lowly, the illiterate and even the vicious, to whom they are bound by the ties of race and sex.” But they go to work. They set about to reclaim and redeem these women, and in doing so to uplift the race.

Jefferson acknowledges that because black Americans live under a system of oppression, a hierarchy has formed in the black community– a ‘Negroland,’ as she calls it. She remembers a boy from her two-week summer camp, simply named ‘R’. They are thrown together, Jefferson thinks, because their counsellors believe that R. would feel more comfortable around somebody like him. Somebody like him translates as they are both black.

At the end of the week my counselor takes me aside. Can I help R. fit in better? she wants to know. Can I talk to him? Everyone is still calling him “the new kid.” I’m mortified. I hate it when I’m supposed to be having fun and Race singles me out for special chores and duties. I will, I tell her, making myself sound agreeable. And I do. I can see the two of us even now, me and him, making trite, labored conversation. Neither of us smiling.

As Jefferson reflects upon this moment, she feels a sense of guilt and shame upon realizing that she looked down on him as being of a class that she did not want to be a part of; a class pitied by those in ‘Negroland’.

Nevertheless, at school, Margo and her sister Denise are the ‘token’ black girls during a time that only a set number of black children were accepted into white schools. Still in the depths of segregation, the girls enter into an atmosphere that has not made room for them, and, as Jefferson explains, her parents must teach and correct them at home. She describes how her mother Irma refused to sugar-coat the instance when a music teacher had the class sing a racist song, whilst during a family vacation, her father Ronald set the example that the family would not bow beneath racist practices when a hotel placed them in an undesirable room.

Nevertheless, at school, Margo and her sister Denise are the ‘token’ black girls during a time that only a set number of black children were accepted into white schools. Still in the depths of segregation, the girls enter into an atmosphere that has not made room for them, and, as Jefferson explains, her parents must teach and correct them at home. She describes how her mother Irma refused to sugar-coat the instance when a music teacher had the class sing a racist song, whilst during a family vacation, her father Ronald set the example that the family would not bow beneath racist practices when a hotel placed them in an undesirable room.

As such, whilst Jefferson spends much time remembering her school days, she also remarks upon the schooling given to her by her parents, who are presented as highly reflective of the ideals of privileged black Americans in striving to give their daughters the best education. Jefferson’s parents sense that their daughters need to excel above their white peers in order to succeed:

Equal opportunity should mean that an audience of Americans would be ready, willing, and eager when you, an unimpeachably outstanding Negro woman, stepped forth to stir, win, command their admiration.

As we see the author develop into adolescence, we witness her aspiring to be like her idols: ballerina Ravel Wilkinson, Sammy Davis, Jr., and the glamorous singers and actresses Lena Horne and Dorothy Dandridge. Yet Jefferson struggles to maintain her black identity in the midst of Western standards of beauty. This struggle to embrace her heritage within an oppressive society dominates Jefferson’s mental space. Throughout the memoir, she describes existing in two worlds each with separate expectations: in ‘Negroland’, she did not want to be associated with the black people that white America pitied or scorned; in white America, she must navigate the demands of academic life, her social life, her camp life – white culture as a whole. These two opposing societies battle for Jefferson’s attention, and that battle wears on her:

We let ourselves become tools of oppression in the black community. We’d settled for a desiccated white fascimile and abandoned a vital black culture. Striving to prove we could master the rubric of white civilization that had never for a moment thought us the best of anything in their life or history.

Woven throughout the memoir is haunting the refrain: ‘Sometimes I forget I am a Negro.’ Jefferson’s mother speaks these words when the author is a young woman, but the statement lingers in Jefferson’s mind, persisting as she matures into adulthood. She continues to be torn apart by the internal battles for her identity throughout the seventies, when feminism flourished but black women were hesitant to join white activists who operated under a different, whiter feminism. As ‘Negroland’ disappeared and blurred with white culture, Jefferson felt her depression, which began in college, begin to deepen. However, in the memoir’s later chapters, she recounts a process of healing, and describes how she began to reclaim her self-worth. In the memoir’s concluding chapter, Jefferson beckons the reader to observe what others expected of her:

Being an Other, in America, teaches you to imagine what can’t imagine you. That’s your first education. Then comes the second. Call it your social and intellectual change. The world outside you gets reconfigured, and inside too. Patterns deviate and fracture. Hierarchies disperse. Now you can imagine yourself as central. It feels grand. But don’t stop there. Let that self extend into other narratives and truths. All of them shifting even as I write.

Negroland is a candid, sometimes brutal, account of the systems of oppression operating in white America. Jefferson begins the memoir with a history lesson in how black people rose above the system of oppression inflicted upon them. It ends with the author reclaiming her identity, and her life.

Jenna Rogers is studying for a masters in prose writing. She graduated from Olivet Nazarene University in 2014 with a degree in English Literature and Creative Writing. After teaching at a language immersion school and a library for a few years, she decided to move to St. Andrews and focus on writing stories. She’s originally from Saint Louis, Missouri, USA.